The Sunday Times featured an op-ed by Mark Britnell, a professor at the UCL Global Business School for Health, with the headline Our creaking NHS can’t beat its admin chaos without a tech revolution. Substitute “U.S. healthcare system” for “NHS” and the headline still would work, as would most of the content.

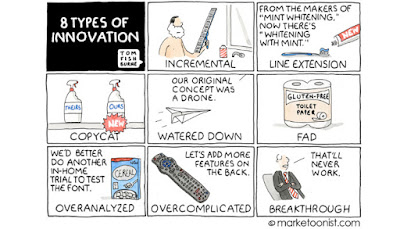

I wouldn’t hold my breath about that tech revolution. In fact, if you’re waiting for disruptive innovation

in healthcare, or more generally, you may be in for a long wait.

The authors looked at data from 45 million scientific

papers and 3.9 million patents, going back six decades. Their primary method of analysis is something

called a CD

Index, which looks at how papers influence subsequent citations. Essentially, the more disruptive, the more

the paper itself is cited, rather than previous work.

The results are surprising, and disturbing. “Across fields, we find that science and

technology are becoming less disruptive,” the authors found, “…relative to

earlier eras, recent papers and patents do less to push science and technology

in new directions.” The declines

appeared in all the fields studied (life sciences and biomedicine, physical

sciences, technology, and social sciences), although rates of decline varied

slightly.

The authors also looked at how language changed, such

as introduction of new words and use of words that connote creation or discovery

versus words like “improve” or “enhance.”

The results were consistent with the CD Index results.

Disruption is declining. Credit: Park, et. alia

“Overall,” they say, “our results suggest that slowing

rates of disruption may reflect a fundamental shift in the nature of science

and technology.”

“The data suggest something is changing,” co-author Russell

Funk, a sociologist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, told Nature.

“You don’t have quite the same intensity of breakthrough discoveries you once

had.”

It’s not all bad news, though. The absolute number of highly disruptive works

was surprisingly consistent over time, but they make up decreasing percentage

of all papers. Fortunately, “declining

aggregate disruptiveness does not preclude individual highly disruptive works.”

|

| Disruption isn't quite dead. Credit: Park, et. alia |

“A healthy scientific ecosystem is one where there's a

mix of disruptive discoveries and consolidating improvements, but the nature of

research is shifting,” Professor Funk said.

“With incremental innovations being more common, it may take longer to make

those key breakthroughs that push science forward more dramatically.”

The authors speculated about a couple possible factors

for the decline. One is that many researchers

face “publish or persist” incentives that reward volume over innovation. “A lot of innovation comes from trying new

things or taking ideas from different fields and seeing what happens,” co-author

Michael Park said.

“But if you are worried about publishing paper after paper as quickly as you

can, that leaves a lot less time to read deeply and to think about some of the

big problems that might lead to these disruptive breakthroughs.”

A second contributor could be a narrowing of

scope. Papers were less likely to cite a

wide diversity of sources, were more likely to cite the paper’s authors instead

of papers by other authors, and tended to cite older works, “suggesting that scientists

and inventors may be struggling to keep up with the pace of knowledge expansion

and instead relying on older, familiar work.”

In any event: “All three indicators point to a consistent story: a

narrower scope of existing knowledge is informing contemporary discovery and

invention.”

Reliance on large research teams has also been cited

as a culprit for the switch towards incremental change over disruption; a 2019 paper by Wang,

et. alia warned “large

teams develop and small teams disrupt.”

“A healthy ecosystem of science and technology is

likely to require a balance of different types of contributions,” Professor Funk

told

Physics World. “The dramatic declines that we observe in disruptive work

suggests that this balance may be off, and that encouraging more disruptive

work could help to push scientific understanding forward.”

The research makes me think about a recent article in MIT

Technology Review by Shannon Vallor:

We

used to get excited about

technology. What happened? “The

goal of consumer tech development used to be pretty simple: design and build

something of value to people, giving them a reason to buy it,” Professor

Vallor laments, “whereas now it is about designing “a product that will extract

a monetizable data stream from every buyer.”

“The fact is, the visible

focus of tech culture is no longer on expanding the frontiers of humane

innovation—innovation that serves us all,” she worries. “Engineering and

inventing were once professions primarily oriented toward creating more livable

infrastructure, rather than disposable stuff.” Now,

she fears, it is all about “Take the money and run.”

Healthcare needs a tech

revolution, as Professor Britnell calls for, and I would argue that it needs

disruption at every level, and instead we’re getting incremental change

instead. Professor Funk would not be

surprised.

Apparently, the same is true for most

scientists as well.

Professor Vallor believes:

“When it stays true to its deepest

roots, technology is still driven by a moral impulse: the impulse to construct

places, tools, and techniques that can help humans not only survive but

flourish together.” There’s nowhere

where that should be more true than in healthcare.

If there has been a common theme in my writing over

the years, it has been that there are good ideas outside of healthcare that

should be considered for it/applied to it.

The new research from Professor Funk and colleagues confirms that disruptive

ideas are out there; they just may not be in the expected field. “Relying on

narrower slices of knowledge benefits individual careers,” the authors noted, “but

not scientific progress more generally.”

Or progress generally.

Disruption is hard.

It’s risky. It won’t come from committees or consensus. But I’m more interested in ideas that jump us

to a 22nd century healthcare system than ones that incrementally just

take us another year from a 20th century one.

No comments:

Post a Comment