I knew what DNA was. I knew what synthetic DNA was. I knew what mirror DNA was. I even knew what eDNA was. But I didn’t know about aDNA, or that the field of study for it is called genomic paleoepidemiology. A new study by one of the pioneers of the field illustrates its power.

|

| Those cows are going to have some surprises for prehistoric humans. Credit: Microsoft Designers |

Our recent

experience with COVID-19 and, currently, with bird flu, should have made

everyone aware that one of the dangers of living with large populations of

animals (like livestock) creates opportunities for diseases to cross over from

those animals to us, often with devastating effect. These are called zoonotic

diseases, and they still kill millions of people each year.

When humans transitioned from hunter/gatherers

to a more pastoral lifestyle, and then to farming, the pathogens had their

chance.

Humans are

thought to have started domesticating animals around 11,000 years ago. “This is

the time when you’re in close proximity to animals, and you get these jumps,”

Dr. Willerslev told

Carl Zimmer of The New York Times. “That was the expectation.” So the

researchers were surprised to find that the earliest evidence of zoonotic

diseases didn’t appear until around 6,500 years ago, and didn’t become widespread

until about 5,000 years ago.

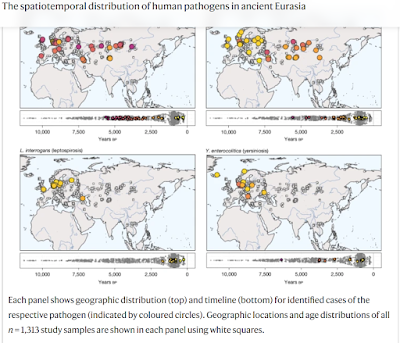

Not

surprisingly, they found evidence of the plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis,

in a 5,500-year-old sample. They also found traces of Malaria (Plasmodium

vivax) -- 4,200 years ago; Leprosy (Mycobacterium leprae) -- 1,400

years ago; Hepatitis B virus -- 9,800 years ago; Diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae) -- 11,100

years ago.

In all, the researchers identified 5,486 DNA sequences that came from bacteria, viruses and parasites. Not bad for DNA from tens of thousands of years ago.

The authors note:

Although zoonotic cases probably existed before 6,500 years ago, the risk and extent of zoonotic transmission probably increased with the widespread adoption of husbandry practices and pastoralism. Today, zoonoses account for more than 60% of newly emerging infectious diseases.

“It’s not

a new idea, but they’ve actually shown it with the data,” says Edward

Holmes, a virologist at the University of Sydney, Australia. “The scale of the

work is really pretty breathtaking. It’s a technical tour de force.”

“We’ve

long suspected that the transition to farming and animal husbandry opened the

door to a new era of disease – now DNA shows us that it happened at least 6,500

years ago,” said

Professor Willerslev. “These infections didn’t just cause illness – they may

have contributed to population collapse, migration, and genetic adaptation.”

The

researchers speculate that populations in the Steppe region were among the

first to tame horse and domesticate livestock at scale, and it was their

migration west that caused the appearance of the zoonotic diseases in the wider

population. Moreover, it seems likely that the Steppe populations had acquired better

immunity for them, unlike the existing populations they encountered. That would

have led to massive population losses and made the Steppe migration much

easier.

Think of

what happened to the indigenous populations of the Americas or Australia when

European settlers first came to their shores, only this time it was the

then-Europeans who were the victims, dying off in huge numbers. Those of “European”

background may need to think further east for their actual heritage.

“It has

played a really big role in genetically creating the world we know of today,”

Dr. Willerslev told

Mr. Zimmer.

This isn’t

just of academic interest. Zoonotic diseases are still very much with us. “If

we understand what happened in the past, it can help us prepare for the future.

Many of the newly emerging infectious diseases are predicted to originate from

animals,” said

Associate Professor Martin Sikora at the University of Copenhagen, and first

author of the report.

Professor

Willerslev added:

“Mutations that were successful in the past are likely to reappear. This

knowledge is important for future vaccines, as it allows us to test whether

current vaccines provide sufficient coverage or whether new ones need to be

developed due to mutations.”

Nonetheless,

as Hendrik Poinar, an expert on ancient DNA at McMaster University in Canada

who was not involved in the study, told

Mr. Zimmer: “The paper is large and sweeping and overall pretty cool.”

Pretty.

Cool. Indeed.

The paper concludes:

Our findings demonstrate how the nascent field of genomic paleoepidemiology can create a map of the spatial and temporal distribution of diverse human pathogens over millennia. This map will develop as more ancient specimens are investigated, as will our abilities to match their distribution with genetic, archaeological and environmental data. Our current map shows clear evidence that lifestyle changes in the Holocene led to an epidemiological transition, resulting in a greater burden of zoonotic infectious diseases. This transition profoundly affected human health and history throughout the millennia and continues to do so today.

As Dr. Poinar

told

Mr. Zimmer: “It’s a great start, but we all have miles to go before we sleep.”

-----------

I’ve long been amazed at what archaeologists

and paleontologists have been able to tell us about our past, based on a few

fossils, bones, or artifacts. I’m even more impressed that we’re recovering

ancient DNA and using it to tell us even more of the story about how we got

here.

It should

be sobering to us all that, as much as we worry about weapons and invasions,

the biggest risk to a population remains infectious diseases, especially

zoonotic ones. The “winner” is the one who happens to have the best immunity.

No comments:

Post a Comment