It’s been almost four years since I first wrote about microplastics; long story short, they’re everywhere. In the ground, in the oceans (even at the very bottom), in the atmosphere. More to the point, they’re in the air you breathe and in the food you eat. They’re in you, and no one thinks that is a good thing. But we’re only starting to understand the harm they cause.

Who knows what microplastics are doing in our body? Credit: Bing Image Creator

The Washington Post recently reported:

Scientists have found microplastics — or their tinier cousins, nanoplastics — embedded in the human placenta, in blood, in the heart and in the liver and bowels. In one recent study, microplastics were found in every single one of 62 placentas studied; in another, they were found in every artery studied.

One 2019 study

estimated “annual microplastics consumption ranges from 39000 to 52000

particles depending on age and sex. These estimates increase to 74000 and

121000 when inhalation is considered.” A more recent

study estimated that a single liter of bottled water may include 370,000

nanoplastic particles. “It’s sobering at the very least, if not very

concerning,” Pankaj Pasricha, MD, MBBS, chair of

the department of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, who was not involved with the

new research, told Health.

But

we still don’t have a good sense of exactly what harm they cause. “I hate to

say it, but we’re still at the beginning,” Phoebe Stapleton, a professor of pharmacology and toxicology at

Rutgers University, told

WaPo.

A

new study sheds

some light – and it is not good. It found that people with microplastics in their

heart were at higher risk of heart attack, stroke, and death. The researchers

looked at the carotid plaque from patients who were having it removed, and

found 60% of them had microplastics and/or nanoplastics. They followed patients

for three years to determine the impacts on patients’ health, and found higher

morbidity/mortality.

“This is

pivotal,” Philip Landrigan, an epidemiologist and professor of biology at

Boston College, who was not involved in the study, wrote

in an accompanying opinion piece. “For so long, people have been saying

these things are in our bodies, but we don’t know what they do.” He went on to

add: “If they can get

into the heart, why not into the brain, the nervous system? What about the

impacts on dementia or other chronic neurological diseases?”

Scary

stuff.

If that

isn’t scary enough, an article last yar in PNAS found: “Indeed, it turns out that a

host of potentially infectious disease agents can live on microplastics,

including parasites, bacteria, fungi, and viruses.” Even worse: “Beyond their

potential for direct delivery of infectious agents, there’s also growing

evidence that microplastics can alter the conditions for disease transmission.

That could mean exacerbating existing threats by fostering resistant pathogens

and modifying immune responses to leave hosts more susceptible.”

However much

you’re worrying about microplastics, it’s not enough.

Marine

ecologist Randi Rotjan of Boston University is blunt: “Cleaning

up microplastics is not a viable solution. They are ubiquitous in our

environment. And macroplastics are going to break down to microplastics for

millennia. What we can do is try to understand the risk” Francesco

Prattichizzo, one of the researchers in the new study, agrees, warning:

“Plastic production is steadily increasing and is projected to continue

increasing, so we must know how [and] if any of these molecules affect our

health.”

That’s easier said than done. As WaPo notes:

Part of the problem is that there is no one type of microplastic. The tiny plastic particles that slough off things like water bottles and takeout containers can be made of polyethylene, or polypropylene, or the mouth-twisting polyethylene terephthalate. They might take the form of tiny spheres, fragments or fibers.

Sherri

Mason, director of sustainability at Penn State Behrend

in Erie, Pa. told WaPo that, when it comes to assigning cause and

effect: “Cigarettes are definitely easier than microplastics.” In the good

news/bad news category, she added: “Probably over the next decade we’ll get a

lot of good data. But we’ll never have all of the answers.”

Unfortunately,

the amount of microplastics just keeps growing. Professor Stapleton told

WaPo: “It’s almost like a generational

accumulation. Forty years ago we didn’t have as much plastic in the environment

as we do now. What will that look like 20 years from now?”

We

can’t even imagine.

|

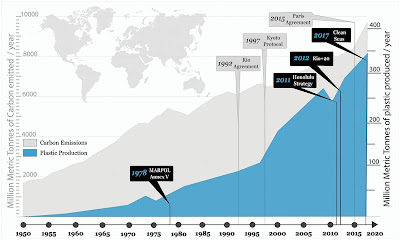

| None of this is good news. Figure from Borrelle et al. (2017) |

“The first

step is to recognize that the low cost and convenience of plastics are

deceptive and that, in fact, they mask great harms,” Professor Landrigan

pointed out. Similarly, Lukas Kenner, a professor

of pathology at the Medical University of Vienna, suggested to WaPo: “I’m

a doctor, and we have our principle: ‘Don’t harm anybody. If you just spill

plastics everywhere, and you have no idea what you’re doing, you’re going

exactly against this principle.”

Microplastics

are similar to cigarettes in that the health risks of the latter were pointed

out years before any action was taken, and even then many people still smoke. It’s

even more similar to climate change, in that we’ve had plenty of warning, and

the impacts are starting to be clear, but the dangers accumulate over such a

long period of time that no one feels compelled to act.

It’s

also like climate change in that the fossil fuel companies bear a significant amount

of the blame. Dr. Londrigan charges: “They

realize that their market for burning fossil fuels is going down, yet they’re

sitting on vast stocks of oil and gas and they’ve got to do something with it. So

they’re transitioning it to plastic.”

Perhaps

biology will save us, with bacteria

eating the microplastics. Or maybe it be robotics, with

nanobots doing the work. But we’ve been talking about engineering our way

out of climate change for thirty plus years, and yet here we are, in climate

crisis. I’m not holding my breath (although I’d ingest fewer microplastics that

way) about fixing microplastics anytime soon.

We’ve

all got a long list of things to worry about, but if microplastics isn’t

already on yours, you should add it.

No comments:

Post a Comment