These are not happy times in America.

Gen Z is not happy. Credit: Bing Image Creator

Now, I’m

not thinking about the increasing cultural wars, the endless political

bickering, the troubles in the Med-East or Ukraine, the looming threat of

climate crisis, or the omnipresent campaigning for the November 2024 elections,

although all those play a part. I’m talking about quantifiable data, from the latest

World Happiness Report. It found

that America has slipped out of the top 20 countries for the first time,

falling to 23rd – behind countries like Slovenia and the U.A.E. and

barely ahead of Mexica or Uruguay.

Even worse, the fall in U.S. scores is primarily due to those under 30. They ranked 62nd, versus Americans over 60, who ranked 10th. A decade ago those were reversed. Americans aged 30-44 were ranked 42nd for their age group globally, while Americans between the ages 45-59 ranked 17th.

It’s not solely

a U.S. phenomenon. Overall, young people are now the least happy, and the

report comments: “This is a big change from 2006-10, when the young were

happier than those in the midlife groups, and about as happy as those aged 60

and over. For the young, the happiness drop was about three-quarters of a

point, and greater for females than males.”

“I have never seen such an extreme change,” John Helliwell,

an economist and a co-author of the report, told

The New York Times, referring to the drop in happiness among younger

people. “This has all happened in the last 10 years, and it’s mainly in the

English-language countries. There isn’t this drop in the world as a whole.”

Jan-Emmanuel

De Neve, director of the University of Oxford’s Wellbeing Research Center and

an editor of the report, said in an

interview with The Washington Post that the findings are concerning

“because youth well-being and mental health is highly predictive of a whole

host of subjective and objective indicators of quality of life as people age

and go through the course of life.”

As

a result, he emphasized: “in North America, and the U.S. in particular, youth

now start lower than the adults in terms of well-being. And that’s very

disconcerting, because essentially it means that they’re at the level of their

midlife crisis today and obviously begs the question of what’s next for them?”

Gen

Z is having a mid-life crisis.

The researchers speculate that social media, political polarization,

and economic inequality between generations contribute to the low scores for

younger Americans. Jon Clifton, CEO of Gallup, believes:

“Young people have more social interactions, but feel more lonely,” and

that they aren’t as connected to their job, churches, or other institutions.

“One factor, which we’re all thinking about, is social

media,” Dr. Robert Waldinger, the director of the Harvard Study of Adult

Development, said

in a NYT interview,. “Because there’s been some research that shows that

depending on how we use social media, it lowers well-being, it increases rates

of depression and anxiety, particularly among young girls and women, teenage

girls.”

Others note the impact of the pandemic. Professor De Neve said: “general negative trend for youth well-being in the United States [was] exacerbated during covid, and youth in the U.S. have not recovered from the drop.” Similarly, Lorenzo Norris, an associate professor of psychiatry at George Washington University, who was not part of the World Happiness study, told NYT:

The literature is clear in practice — the effect that this had on socialization, pro-social behavior, if you will, and the ability for people to feel connected and have a community. Many of the things that would have normally taken place for people, particularly high school young adults, did not take place. And that is still occurring.

“It’s a

very complex time for youth, with lots of pressures and a lot of demands for

their attention,” Professor De Neve diplomatically

observed. It was not true in all

countries that younger people were the unhappiest, and Professor De Neve

suggests: “I think we can try and dig into why the U.S. is coming down in terms

of wellbeing and mental health, but we should also try and learn from what,

say, Lithuania is doing well.”

Did you

ever expect Lithuania might be a role model for our young people?

Amidst

all the gloomy findings, the report did say: “The COVID crisis led to a worldwide increase in the

proportion of people who have helped others in need. This increase in

benevolence has been large for all generations, but especially so for those

born since 1980, who are even more likely than earlier generations to help others in need.” They may be less happy, but Gen Z and millennials

aren’t less charitable.

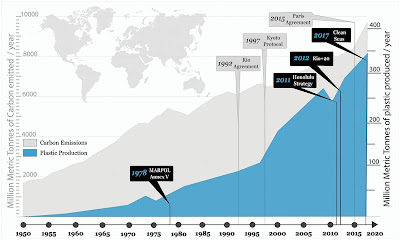

Honestly,

if young people aren’t depressed, they’re not paying attention. Social media is

dominating their lives, whether Instagram is making them feel depressed or TikTok

is driving them to harmful mental health content. They can see the impacts of

climate change but not any sign that their elders plan to do anything about it.

Their jobs are neither satisfying nor economically viable enough to allow them

to build wealth, especially when suffering from crushing student loans. They don’t

expect Social Security to help with their retirement, whenever that may be

and whatever that might look like. They have no reason to think that the

largely geriatric politicians understand them or their needs.